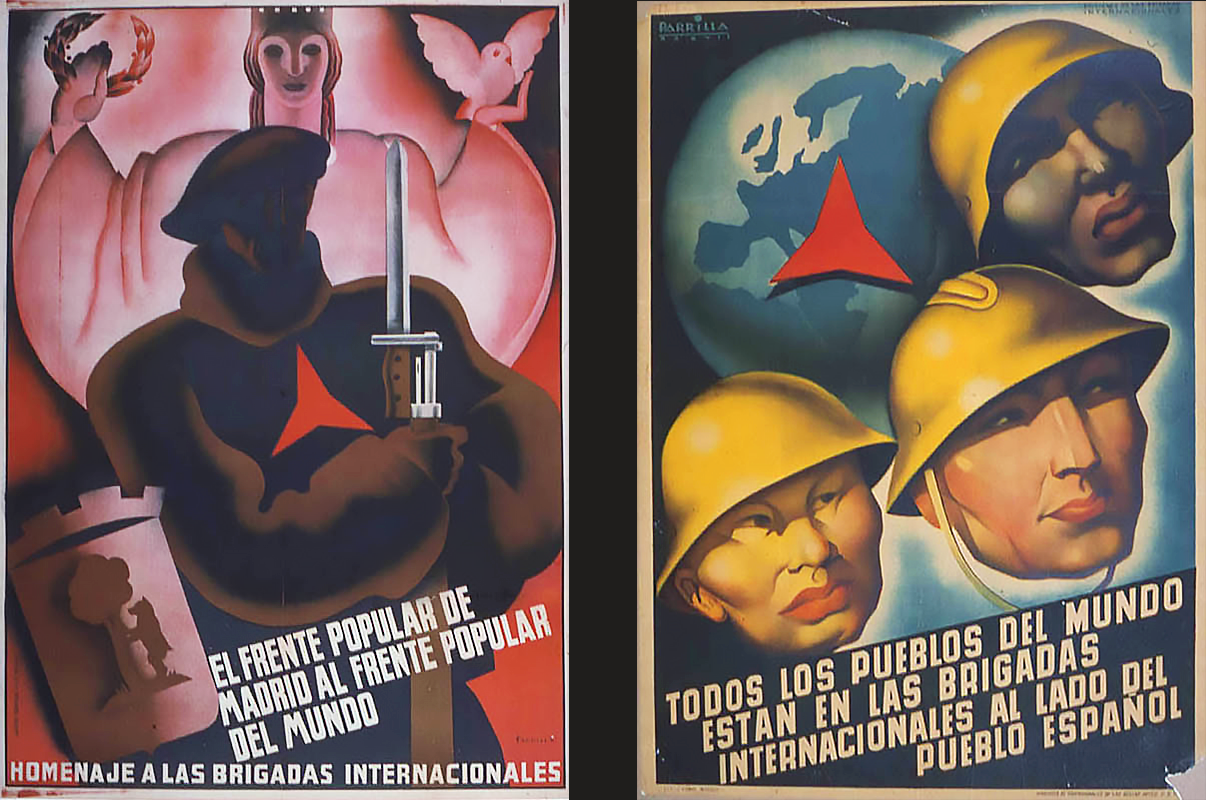

The 1930s began ominously for Europe. Economic upheaval, widespread unemployment, social instability, and the uncertainty of the middle classes paved the way for fascist parties to rise to power in Italy and Germany. In Spain, widespread discontent led to the proclamation of the Republic in 1931. When the army, led by Francisco Franco, rebelled against the legitimate government with the aim of "restoring the order", tens of thousands across Europe mobilized to protect the young Republic. Some of the youth arriving for the Barcelona Workers' Olympics immediately took up arms, followed by leftists, socialists, and anarchists from the world, while the Comintern began actively recruiting members and sympathizers from communist parties.

There were no accurate records of those heading to or arriving in Spain. Scholars estimate their numbers between 30,000 and 40,000. Their identities are often obscure; many lived under false names or identities, even while in exile. Nationalities are also uncertain, as records often list them by place of residence. Due to political tensions, many did not join the Brigades but fought in other units of the Republican Army.

The brigadistas included experienced soldiers who had fought in World War I, as well as young people driven by enthusiasm and a sense of adventure, eager to join the fight for a just the good cause. Among them were NKVD spies too fulfilling the Soviet Union's revolutionary mission, and also drivers, doctors, and writers like Orwell, Hemingway, Malraux, and Arthur Koestler, who were motivated by a moral rebellion against oppression.

The story of the brigadistas ended when the fighting parties agreed to withdraw foreign supporters. The International Brigades were given a spectacular farewell ceremony in the streets of Barcelona on October 28. In front of 300,000 people, the brigadists paraded along Avenida del Catorce de Abril, in a deeply emotional atmosphere. "You are history, you are legend, you are the noblest chapter in the lives of the working class, the Spanish people, and all humanity," declared Dolores Ibárruri, in words that became legendary. The people bid them farewell with applause, tears, and roses strewn along the path.

The fight in which they were militarily defeated but morally victorious went beyond the defense of Spanish democracy; it was part of a broader anti-fascist movement that resonated across the world. This international solidarity foreshadowed the anti-fascist coalition that would eventually bring down Hitler and Mussolini.

SIZE OF THE ARMED FORCES AND THE INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES

During the Spanish Civil War, the size of both the Nationalist and Republican armies changed significantly. At the outbreak of the war in early 1936, the Nationalists had approximately 32,000 troops on the peninsula, along with an additional 30,000 soldiers from the Army of Africa, who fully supported the insurgents. By 1937, the Nationalist forces had grown to 500,000 soldiers, and by the end of the war in 1938, their numbers had surpassed one million.

The Republican army initially had a force of 66,000 troops, of which 34,000 were located in the Republican zone. By early 1937, the Republicans had increased their forces to 350,000, reaching nearly 750,000 by 1938. Throughout the war, both sides continuously bolstered their armies through large-scale conscription and volunteers from various backgrounds and sources. (Thomas, 1961.)

Various sources estimate the number of volunteers in the International Brigades to be between 30,000 and 50,000. The most recent monograph by Giles Tremlett estimates a total of 35,000 volunteers. (Tremlett, 2020.)

The Spanish Civil War began in July 1936 when the Nationalists rebelled against the Republican government. The International Brigades arrived later that year to support the Republicans against the Nationalist forces. They played a crucial role in the defense of Madrid, managing to halt the Nationalist advance.

In 1937, the Brigades were involved in the battles of Jarama and Guadalajara, where they suffered heavy losses but succeeded in repelling the Italian fascist troops. Despite their efforts, the Republicans could not achieve a decisive victory. That same year, the Nationalists captured key industrial centers in the north, such as Bilbao and Santander, gaining significant territorial advantage.

In 1938, the Nationalists continued their advance and seized Aragon. The Brigades' last major battle was the Battle of the Ebro, where the Republicans attempted to reclaim lost territory but ultimately faced defeat. By early 1939, Franco's forces captured Barcelona and Madrid, securing a Nationalist victory. The Civil War ended in April when the Republicans surrendered, paving the way for Franco’s dictatorship.

July 1936

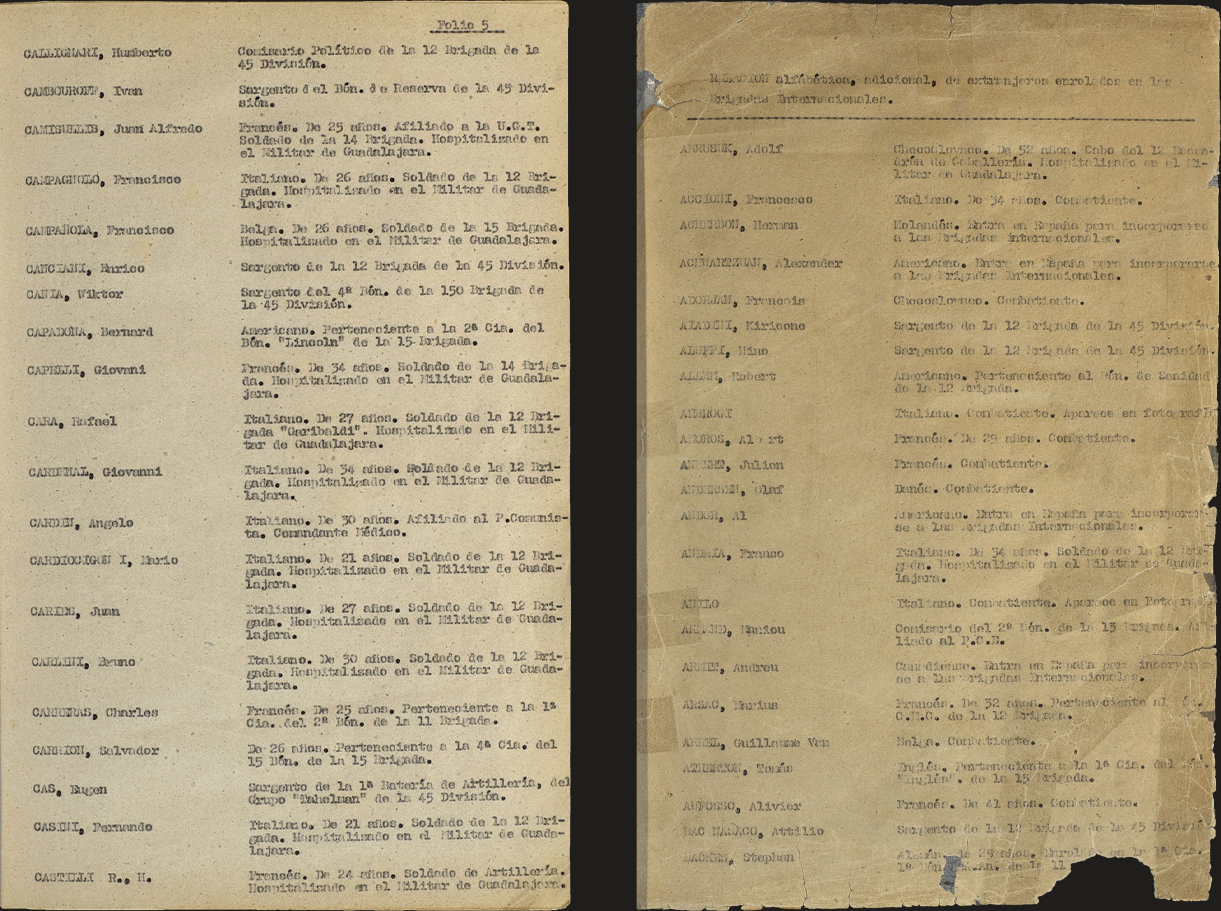

We have digitized the Relación alfabetica de extranjeros enrolados en las Brigadas Internacionales list and organized the data into a database. It is important to emphasize that the list is incomplete, which is evident from the number of fighters listed (11,687). Further in-depth research is needed to determine the circumstances of its creation. Whether it represents a snapshot in time or is the result of military administrative shortcomings, it is clear that we are missing a lot of names of individuals who are known to have fought throughout the Civil War and left Spain alive.

The general uncertainty surrounding the identity and number of the brigadistas makes the Salamanca list valuable as a supplementary source, particularly as it includes details such as the brigadistas' age, nationality, occupation, and military unit. From this data, we were able to create a visualization that reflects not only their geographic distribution but also provides insights into their social backgrounds.

The volunteers came from over 65 countries, reflecting the diverse social and cultural backgrounds of the international community. The largest numbers came from France, Germany, Italy, as well as the United States and the United Kingdom. Regarding ethnocultural background, the number of Jewish volunteers was notably high—just one year after the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. Many of them fought to confront the looming threat of fascism. This offers an alternative narrative to the traditional story of Holocaust passivity, as many Jews consciously chose to fight fascism in Spain. Volunteers of African, Asian, and Arab descent also participated, along with Black Americans, some of whom were among the first to lead white soldiers in battle.

Below is a list of the volunteers by their nationality.

French: 1561

American: 1011

Italian: 875

Polish: 722

English: 706

German: 664

Czechoslovak: 415

Austrian: 369

Belgian: 425

Yugoslavian: 258

Canadian: 245

Dutch: 168

Russian: 145

Swiss: 135

Hungarian: 123

Swedish: 105

Other: 505

No nationality data: 3355

The following map shows the same nationality breakdown, connecting Spain with the nationality assigned in the database. Click on any of the lines to read the list of names relating to that nationality.

Read about notable people tied to the Spanish Civil War. To read their biography, click on their portrait on the map.

The age distribution among the International Brigades' volunteers varied, with most being young adults, typically in their 20s to early 30s. Due to their youth, many had no prior combat experience, receiving their primary military training only after arriving in Spain. In contrast, older volunteers, some of whom were veterans of World War I, often took on leadership and training roles, leveraging their battlefield experience to adapt more quickly to combat conditions. This lack of experience posed challenges, especially early on, but the presence of WWI veterans helped enhance the brigades’ overall combat readiness over time.

The volunteers of the International Brigades largely comprised miners and manual laborers, reflecting a strong working-class presence, especially from major European industrial centers. Alongside these core groups were intellectuals, teachers, students, and artists, adding to the diversity. The brigades also included professionals like doctors, lawyers, and engineers, who brought specialized skills to support the cause. This varied composition highlights that while volunteers spanned different economic and social strata, many were motivated by a shared working-class solidarity and a determination to resist fascism. The brigades symbolized a unique convergence of blue-collar workers and other professions dedicated to this common fight.

Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War: Revised Edition. Modern Library, 2001.

Tremlett, Giles. Las brigadas internacionales: Fascismo, libertad y la Guerra Civil Española. Debate, 2020.

The Relación alfabética de extranjeros enrolados en las Brigadas Internacionales was processed as part of the Archives as Traces of Migration Creative Europe Project and the bilateral agreement between the Spanish and Hungarian state archives. Budapest-Madrid-Salamanca, 2024.

Coproduction partners:

Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár (National Archives of Hungary)

Subdirección General de Archivos Estatales del Ministerio de Cultura (General Subdirectorate of State Archives of the Ministry of Culture): Documentary Center for Historical Memory (Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica)

Author and chief-editor:

Zoltán Szatucsek

With the collaboration of:

Cristina Díaz Martinez

Ferenc Jeges

István Hegedűs

Manuel Melgar Camarzana

Severiano Hernandez Vicente

Design:

Attila Bátorfy

Krisztián Szabó

Opening video:

Despedida de las Brigadas Internacionales en Barcelona el 28 de octubre de 1938 (Farewell to the International Brigades in Barcelona (Oct. 28, 1938)) Source: YouTube